The Soibhan Dowd Trust Memorial Lecture: The Slipping Glimpse

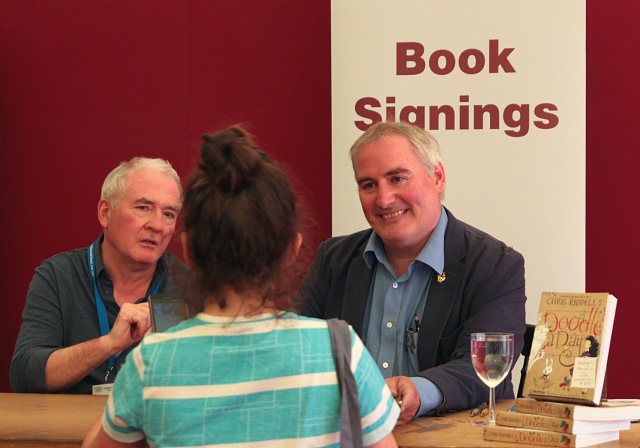

Chaired by Tony Bradman

This is the third year of the book festival hosting the Soibhan Dowd Trust Memorial Lecture, the previous speakers being Patrick Ness and Matt Haig. The trust funds projects that bring books to underprivileged children and, as the Children’s Laureate, Chris Riddell spends a great deal of time bringing books and their illustrations to children all over the country. He seems proud to be giving the lecture and to have met Soibhan Dowd, however briefly. Six weeks after they met at a party he opened the Guardian to see her obituary and felt a great sense of loss that he had only managed the briefest glimpse of her and her mind.

The event had started late because they had been hoping to set up a display so that he could draw and have every line projected onto the large screen behind him. Presumably the aim was to emulate his recent forays into live drawing on Periscope. The display refused to work and was replaced by a flip chart and a pencil, which sadly remained untouched until the questions.

His work as an illustrator might be celebrated now, but it wasn’t at school. He went to the kind of school where art was considered a remedial subject. The kind of class you were sent to if you were troublesome, or they didn’t quite know what to do with you. Riddell loved art and excelled, but was forced to create academic links to legitimise his continued presence in such a remedial class. He was all set to go to university, when the art master declared him a natural illustrator and suggested he apply to art school. Applying to Epsom School of Art and Design a week before courses started worked out for him, much to the dismay of his school since he had won the school English Prize. Students returning to the school to accept a prize at Speech Day could select the book they would be presented with. Riddell’s request for Where The Wild Things Are was clearly met with disapproval, and when the day came the headmaster handed him the school library’s dusty copy of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Riddell accepted it and left the auditorium, walking straight into his art master who took the first book and handed him Where The Wild Things Are.

By the time Riddell finished at Epsom, he was twenty-two and knew everything, setting off to ‘audition’ publishers in London. He walked into multiple offices, rolling out huge charcoal drawings illustrating Gormenghast. He received vague interest but nothing more, until one asked ‘I can see you’ve been taught to draw, but where are your stories?’ Riddell stammered that he’d left his story at home and promptly rushed back to write one. Returning the next day with a short, illustrated story got the response of ‘This is fine, we’ll publish it’ and he found he had walked into the world of children’s books.

Some years later the Economist called asking for illustrations for twelve articles on the EU, a job that resulted in 9 years of work after the initial article run had finished. Work at the Economist was fun and he describes the office as being similar to a gentleman’s club full of clever, if impractically eccentric, people funded by very expensive advertising space. Everyone’s doors were always open, though that didn’t necessarily mean it was a good idea to just stroll in. Riddell once fell over an editor who was lying across the threshold of his office, staring at the ceiling while he tried to compose an article. Work with the Sunday Correspondent and the Independent followed, before children’s books called his name and he returned to publishing.

When he first mentioned The Slipping Glimpse as the title of his lecture, it seemed as though he was referring to his brief glimpse of Soibhan Dowd. He was in fact referring to something else entirely. He describes the experience of attending the kind of publishing world party where there’s plenty of white wine and everyone wears a name tag. At such events there are some who repeatedly receive the same reaction. Someone will start towards them, as if coming to start a conversation, their eyes will slip below the neckline to read the name tag, and then, at the last moment, move on as they change their direction to a more interesting name tag and its owner.

At one such party Riddell found that he and one other man were the main targets of that evening’s slipping glimpses. Recognising him as the father of another child at his son’s nursery, he went over to introduce himself and suggest they leave. A conversation about books they’d loved as children on the train home eventually turned into two book series, the Rabbit and Hedgehog books and the Edge Chronicles, the last book of which comes out soon.

At one point during his work on those series Bloomsbury called asking if he would like to work with a different author. The manuscript they sent him to illustrate was The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman. It was a job that blossomed into a wonderful working relationship, producing some truly stunning illustrations, recognition outside the world of children’s books and newspaper cartoons, and a great deal of mutual reblogging on Tumblr. Riddell views Gaiman as a kind of Gandalf figure (Riddell, of course, is Bilbo), inviting him on an adventure every time he hands over a batch of his words and lets him draw whatever he likes to accompany them. Sometimes it’s not even a manuscript. Riddell will take a quote from an interview or a short piece of writing and craft an illustration around it. After all, as he says: “I get to do a big monster and a sword wielding princess, what’s not to like?”

The online reaction to his illustration of Gaiman’s words led Riddell to seek out other quotes from other writers. Recent attacks on libraries meant he gravitated towards quotes discussing the value of libraries and librarians. In many areas libraries are the centre of the community and the only places some people can go to access both information and companionship. To stifle art is to stifle society and strangle social mobility. When we close libraries it is art and the community surrounding it that we kill. He emphasises that without books and libraries thousands are secluded even further from those around them and further impoverished. This is exacerbated by the fact that the libraries in poor areas where they are needed most are often the first to close.

Children in particular need an escape, and a resource that they can use to dream and learn. We can push children to do ever better in exams, to learn and recite ever increasing numbers of facts, but we cannot ignore the damage being done. An excellent mark on a difficult exam is worthless if it comes at the expense of the child’s current and future health. Another author whose words Riddell has illustrated has encountered this issue time and time again: “sometimes they get good marks, sometimes they cut themselves…we are experiencing an assault on childhood.” Riddell, like many other authors, seems to feel very strongly about the importance of libraries and their preservation. After all, libraries are the gateways to culture and community, education and social mobility. When a library is killed, many other things go with it.